The Land of Palestine in the Time of Jesus

Insights From Some Ancient Historians & Other Sources

Apologies for the late posts this week! It’s been a busy week with an annual district event within my denomination. It was a great time to get some business done as a district, especially electing a new district leader (what we call superintendents in my tradition). My district ministerial license was also renewed for another year thanks to the recommendation of my local church and district boards. This is a stepping stone toward ordination. I’m still in the mood to learn, and I hope you are too!

The land of Palestine is the geographical backdrop to understanding Jesus and the Gospels. What was the land of Palestine like around the first-century? What about the land of Israel? This post will consist of a diet of Tacitus, Josephus (a very healthy portion), the Mishnah, and Psalms of Solomon. This post comes out of my reading of Readings from the First-Century World: Primary Sources for New Testament Study, edited by Walter Elwell and Robert Yarborough.

Insights From the Sources

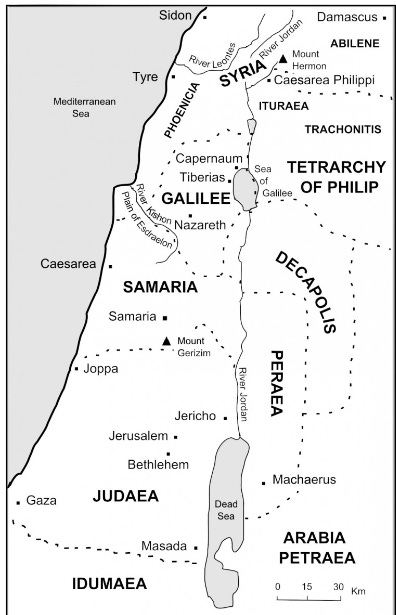

There’s a strong impression from the Roman historians Tacitus and Josephus that the land of Palestine as a whole was very fertile and grew an abundance of vegetation, particularly trees and fruit. Palestine was, for the most part, an agrarian country. During this time, the Jewish Roman loyalist and historian, Josephus, tells us that the plains of Perea, especially, “are covered with a variety of trees, olive, vine, and palm being those principally cultivated.”1 Perea and Galilee were regions very significant to Jesus’ life and ministry, and Machaerus in Perea is where John the Baptizer was executed by Herod Antipas early in Jesus’ ministry. Herod Antipas, or Herod the Tetrarch, one of the four sons of Herod the Great, administrated these regions from 4 B.C. to A.D. 39. He was favored by Ceasar Tiberius and built a city called Tiberius after his name, which Herod made the capital of his kingdom.2 Jesus made his ministry headquarters in the same region in Capernaum, which is just north of Tiberius in Upper Galilee.3

These cities were on the coast of the Sea of Galilee, which was also called the lake of Gennesaret.4 Josephus tells us that “its waters are sweet, and very agreeable for drinking.”5 The plains of Gennesaret grew walnuts, figs, and olives.6 South of Galilee (or Lower Galilee) and Judea is the country of Samaria. Josephus tells us that Samaria

is entirely of the same nature with Judea; for both countries are made up of hills and valleys, and are moist enough for agriculture, and are very fruitful. They have abundance of trees, and are full of autumnal fruit, both that which grows wild, and that which is the effect of cultivation.7

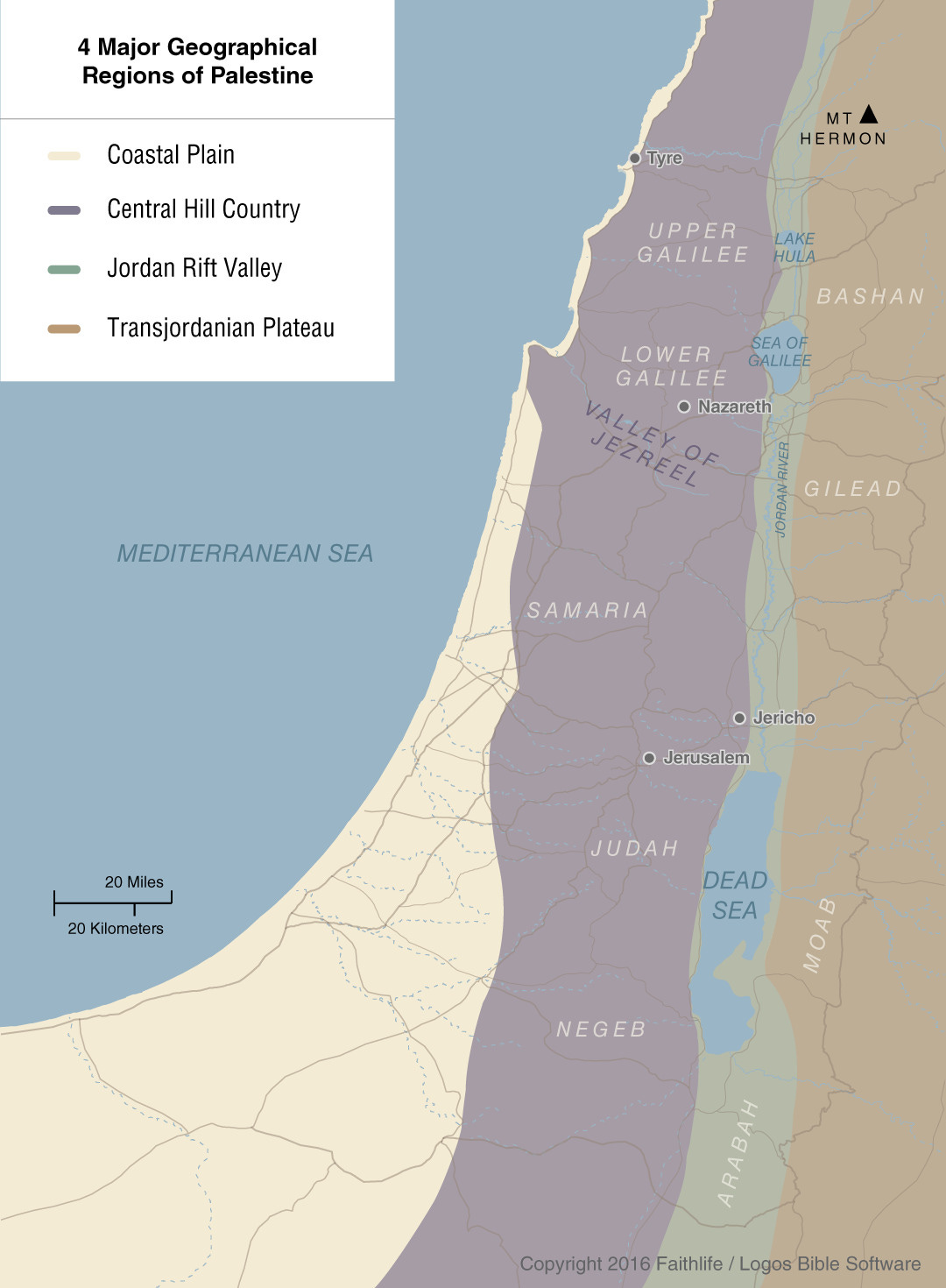

The map below provides a general idea of the topography of the land. The basic idea is that from the coast going east, you’ll find a hilly region followed by a valley that nests the Jordan River, followed by the physical features of a high, elevated, and flat plain.

If you keep going south from Samaria, you’ll be in Judea, on the west side of the Jordan River and Dead Sea, it continues to span west to the Mediterranean Sea. Significant here is the capital and royal city of Jerusalem, which was intentionally made as the center of the region.

Jerusalem was easily the most important city in biblical times. Both God dwelled at the Temple and it’s where Jesus was crucified and resurrected. In Revelation, the “new Jerusalem” is where heaven comes down to earth.8 Josephus tells us that the city had three towers (seen in the upper city on the map above) and walls (labeled on the map). The three towers were named after Herod the Great’s closest relationships (his wife (Mariamme), brother (Phasaelus), and friend (Hippicus)).9 His grandson, Herod Agrippa I, ruled Judea and Samaria A.D. 41-44. During this time, Agrippa expanded the city with a third wall and called it the “New City” or Bezetha.10

But what is perhaps the most important part of Jerusalem is that it reflected the holiness of Israel. A significant source for understanding this is the Mishnah, which is considered the first major work of rabbinic literature, compiled around 200 A.D., documenting a variety of legal opinions in the oral tradition. According to the Kelim (vessels) tractate, there are ten degrees of holiness, with the land of Israel itself being holy and with the Holy of Holies being the most holy part or highest degree of Israel.11 As the degrees are described, it seems to me that the land of Israel reflects the structure of the tabernacle and outer camps or settlements in the scroll of Numbers, and the degrees reflect holiness according to the Levitical purity laws and categories.

The future hope, holiness, and glory of the land of Israel is reflected in the pseudepigraphical12 work around the first-century called the Psalms of Solomon. Psalm 17 of this collection talks about the anticipatory return of all God’s holy people to Israel led by a messianic figure from the offspring of David. According to this psalm, this messianic figure

will gather a holy people whom he will lead in righteousness,

and he will judge tribes of the people sanctified by the Lord its God.

And he will no longer permit injustice to dwell among them,

and no person who sees wickedness will dwell with them.

For he will know them, because all of them are sons of God,

and he will divide them among their tribes upon the earth.

And no longer will an expatriate or foreigner dwell among them;

he will judge peoples and nations by the wisdom of his righteousness.13

While this collection isn’t considered canonical in many traditions, mine included, nor is it found in the Tanakh, the psalm provides a good idea of a popular theology about the future glory of Israel during the time of Jesus.

Concluding Thoughts

As a reminder, this is about exploring the background of Jesus and the Gospels, in particular, according to the text I’m using for this study. Reading the primary sources, while in English, was a fascinating and empowering experience. I imagine some interpretative elements and strategies would only improve the reading of these primary sources from a historical perspective, but I know that I’ve only scratched the surface of learning from these sources. Next, we’ll look at the history of the Jews.

Bibliography

Brannan, Rick, Ken M. Penner, Israel Loken, Michael Aubrey, and Isaiah Hoogendyk, eds. The Lexham English Septuagint. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012.

Elwell, Walter A. and Robert W. Yarbrough, eds. Readings from the First-Century World: Primary Sources for New Testament Study. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic Press, 1998.

Josephus, Flavius, and William Whiston. The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987.

Josephus. The Jewish War: Books 1–7. Edited by Jeffrey Henderson, T. E. Page, E. Capps, and W. H. D. Rouse. Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray. Vol. 203, 487. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA; London; New York: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann Ltd; G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1927–1928.

Rath, Julia. “Psalms of Solomon - Bible Odyssey.” Bible Odyssey, 16 January 2024. https://fr.bibleodyssey.com/articles/psalms-of-solomon/.

Tacitus, Cornelius. Historiae (Latin). Edited by Charles Dennis Fisher. Medford, MA: Perseus Digital Library, 1911.

Josephus, Jewish War 3.3.3 § 45.

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.2.3.

Mt 4:13;

Lk 5:1; JW 3.10.7 § 506.

Ibid.

JW 3.10.8 § 517.

JW 3.3.4-5 §§ 48-49.

Rv. 21:1-4.

JW 5.4.1-3 §§ 160-170.

JW 5.4.1-3 §§ 148 and 151.

“Mishnah Kelim 1:6-9,” Sefaria.org, 2024, https://www.sefaria.org/Mishnah_Kelim.1.6?lang=bi&with=all&lang2=en. The degrees of holiness can be represented as Israel - Walled Cities - Wall of Jerusalem - Temple Mount - The Rampart - Court of the Women - Court of the Israelites - Court of Priests - The Porch and Altar - Sanctuary - Holy of Holies.

“Pseudepigraphy” is essentially the practice of an author writing literature in another person’s name, or is attributed to someone else other than the original author. We know the Psalms of Solomon were not written by Solomon because he predates the date of the literature by hundreds of years, and so is considered by most scholars to be written by another, anonymous, author.

Rick Brannan, Ken M. Penner, et al., eds., The Lexham English Septuagint (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2012), Ps Sol 17:28–31.